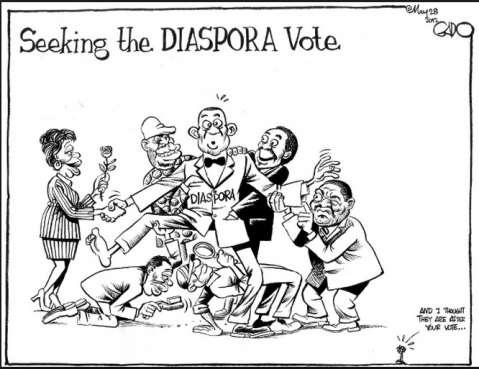

The Zambia Civic Education has observed that calls to have Zambians living abroad given the right to vote should be accompanied with modalities to curb malpractices.

Executive Director Judith Mulenga has told QFM News in an interview that such calls are welcome considering that they are meant to allow Zambians abroad to also exercise their right to vote even if they are not within the country.

Ms Mulenga says if such a system is to be introduced, there is need to ensure that measures are put in place to curb any malpractices.

She says such a system should not be viewed as an avenue for rigging the reason why all political parties and other stakeholders should also contribute how best the system can be handled.

QFM

Should Citizens Living Overseas be Allowed to Vote?

By diasporaalliance.org

Should expatriates be able to vote in their native countries, months or years after having left? Pressure is coming from disenfranchised citizens themselves, who are making their requests in a variety of ways: Egyptian expatriates took to the streets in cities to protest for the right to vote in the post-Arab Spring elections; Greek expatriates have developed a slick campaign video; Malaysian, British, and Kenyan citizens have gone to court; and online petitions have been developed by expats from a number of countries including Uganda, Ireland, Zimbabwe, and Hong Kong.

An increasing number of nations are saying “yes” to overseas voting. Governments are listening to their diasporas and implementing various forms of external voting through absentee postal ballots, proxy voting, and ballot stations in consulates. A 2007 study by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance “Voting from Abroad: The International IDEA Handbook” surveyed international practices on external voting. The report shows that 115 nations and territories allow their citizens to vote while living abroad and since then, the number has been rising. Some countries have specific representatives for their diasporic citizens, while others allow expats to vote in the last constituency in which they lived. Nations allow voting in presidential and general elections and referendums in varying combinations. In short, an increasing number of governments are striving to help their overseas citizens maintain a political role in their home countries. For example, in 2010, while announcing his decision to work toward giving expatriates the vote, Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh said, “I recognize the legitimate desire of Indians living abroad to exercise their franchise and to have a say in who governs India.”

But is this desire legitimate? Some opponents of overseas voting argue that citizens who move abroad are not impacted by their home government’s decisions, so it is more democratic that voting be reserved for resident citizens. Others suggest that only overseas citizens of the small number of countries that levy tax on their expatriates, such as the United States, should be allowed to vote; arguing that it is taxation, rather than citizenship, that entitles an individual to governmental representation.

However, as a long-time advocate of voting rights for Irish emigrants, I hold a different view. Ireland is one of the few countries in Europe that does not allow emigrants to vote in its country’s elections. Both of my parents were born in Ireland, and like all citizens of the country – then and now – they lost their right to vote back home as soon as they immigrated to the United States. During the fifteen years I lived in Ireland, my dual citizenship allowed me to vote in both American and Irish elections. However, like my parents, I also lost my right to vote in Ireland’s elections when I left the country last year.

Though I have known about Ireland’s policy on emigrant voting rights for many years, I did not fully understand the policy’s implications until the last decade or so. The Irish government has been working to enhance the relationship with the Irish abroad – through innovative and supportive methods – in innovative and supportive ways. It has brought in some policies that have increased support for the most vulnerable, and introduced new channels of communication for expat business people and others eager to assist back home. Yet there are are limitations to even the most well-intentioned of top-down policies. While several of Ireland’s elected representatives have themselves lived abroad, and sincerely care about our overseas citizens, it has become clear to me that enabling the Irish abroad to elect representatives would add nuance and accountability to Ireland’s understanding of the emigrant experience – and that would ultimately enhance the general welfare of the entire community of Irish citizens, at home and abroad.

Many expatriates view themselves as only temporarily departing their home shores, and many of them maintain interests in their home countries even after they migrate. The economic crisis brought on by the collapse of the housing boom compelled 87,000 people to emigrate from Ireland last year. Many of them are Irish citizens hoping to return at the earliest possible opportunity, yet they will not be able to if Ireland’s unemployment levels remain high and concerns about accessing adequate housing, education, and healthcare persist. Their absence from the country negate neither their interest in Ireland’s future nor their stake in it.

Even those that intend to stay abroad for the foreseeable future are affected by decisions made back home. Without any representative in the government that can speak for—and be accountable—to overseas citizens, their interests may simply be sidestepped. Just as opponents of overseas voting sometimes argue that expats should be disenfranchised because they will not adequately consider the experience of those at home and may not be fully informed about domestic issues, we cannot expect voters at home to consider or understand the effects of political decisions on absent citizens.

Another reason that I support overseas voting is that it gives an equal voice to all citizens living abroad. As governments intent on wooing wealthy expatriates open more channels for business executives and other highly successful people abroad, I fear that countries’ engagement strategies will unjustly privilege the voices of some members of the diaspora over others. Wealthy, well-connected individuals will be able to ensure their interests are represented, while the voices of ordinary citizens will go unheard. Granting voting rights to all overseas citizens will not solve all issues of equality in the political sphere, but it will go a long way towards leveling the playing field.

As nations work to enhance their relationships with their diasporas, they are likely to come under increasing pressure to grant their overseas citizens voting rights. It will be difficult for countries to keep asking their expats for economic help while refusing to allow them all a political outlet—particularly when expatriates are likely to be more mobile, more informed, and more connected than ever. Enabling political representation will result in greater understanding of and responsiveness to the experience of all citizens, and the further strengthening of already strong ties.

About the Author: Noreen Bowden writes about emigration and diaspora issues at GlobalIrish.ieand GlobalIrishVote.com. She is the former director of Ireland’s Emigrant Advice Network. Noreen recently graduated from the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University with a Masters in Public Administration.

The contents of this blog are the sole responsibility of the author and its ideas and opinions do not necessarily reflect those of International diaspora Engagement Alliance, the U.S. Department of State, the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Migration Policy Institute, or any of their partners.

JOIN DRIVERN TAXI AS PARTNER DRIVER TODAY!

JOIN DRIVERN TAXI AS PARTNER DRIVER TODAY!